Highlights & Annotations

“Living in a dream of a future is considered a character flaw. Living in the past, bathed in nostalgia, is also considered a character flaw. Living in the present moment is held as spiritually admirable, But truly ignoring the lessons of history or failing to plan for tomorrow are considered character flaws.

I still needed to record the present moment before I could enter the next one, but I wanted to know how to inhabit time in a way that wasn't a character flaw.

Remember the lessons of the past. Imagine the possibilities of the future. And attend to the present, the only part of time that doesn't require the use of memory.” (27)

“When I was twenty-three I began seeing a psychotherapist because I couldn’t bear the idea that, after the end of an affair, all our shared memories might be expunged from the mind of the other, that they might no longer exist outside my own belief they’d happened.

I couldn’t accept the possibility of being the only one who would remember everything about those moments as carefully as I tried to remember them.

My life, which exists mostly in the memories of the people I’ve known, is deteriorating at the rate of physiological decay. A colour, a sensation, the way someone said a single word – soon it will all be gone. In a hundred and fifty years no one alive will ever have known me.

Being forgotten like that, entering that great and ongoing blank, seems more like death than death.” (37)

“Could I claim a memory even if it i couldn’t access it via language? Or was I writing as if it never had happened?

I didn’t mind that perception is partial or that recollection is worse, but I minded that I didn’t know why I remembered what I remembered – or why I thought I remembered what I remembered.” (39)

“The experiences that demanded I yield control to a force greater than my will – diagnoses, deaths, unbreakable vows – weren’t the beginnings or ends of anything. They were the moments when I was forced to admit that beginnings and ends are illusory. That history doesn’t begin or end, but it continues.

For just a moment, with great effort, I could imagine my will as a force that would not disappear but redistribute when I died, and that all life contained the same force, and that I needn’t worry about my impending death because the great responsibility of my life was to contain the force for a while and then relinquish it.

Then the moment would pass, and I’d return to brooding about my lost memories.” (41)

“The catalog of emotion that disappears when someone dies, and the degree to which we rely on a few people to record something of what life was to them, is almost too much to bear.” (43)

“Time kept reminding me that I merely inhabit it, but it began reminding me more gently.

In a dream I found an old-fashioned windup metronome on my desk. A man’s voice behind me: Is that really a metronome on your desk?

In another dream an old woman told me that at my age, she wished she’d known that the soul never stops appearing.” (59)

“Left alone in time, memories harden into summaries. The originals become almost irretrievable.

One day the baby gently sat his little blue dog in his booster seat and offered it a piece of pancake. The memory should already be fading, but when i bring it up I almost choke on it – an incapacitating sweetness.

The memory throbs. Left alone in time, it is growing stronger.

The baby had never seen anyone feed a toy a pancake. He invented it. Think of the love necessary to invent that. In a handful of years he’ll never do it again. An unbearable sweetness.

The feeling strengthens the more i remember it. It isn’t wearing smooth. It’s getting bigger, an outgrowth of new love.” (73)

“...how could I have believed that if I tried hard enough, I could remember everything?” (78)

“I wrote about an illness once I was seven years into a remission that lasted four more.

I didn’t know it yet, but the illness, which still isn’t over, wasn’t the real problem. Thinking about it was the problem, and I don’t think about it anymore. Not in the obsessive, all-consuming way I used to.

I used to harbor a continuous worry that I’d forget what had happened, that I’d fail to notice what was happening. I worried that something terrible would happen because I’d forgotten what had already happened.

Perhaps all anxiety might derive from a fixation on moments – an inability to accept life as ongoing.” (79)

“The best thing about time passing is the privilege of running out of it, of watching the wave of mortality break over me and everyone I know. No more time, no more potential. The privilege of ruling things out. Finishing. Knowing i’m finished. And knowing time will go on without me.

Look at me, dancing my little dance for a few moments against the background of eternity.” (81)

- Is it an ego thing then? This worrying about death?

“Often I believe I’m working toward a result, but always, once I reach the result, I realize all the pleasure was in planning and executing the path to that result.

It comforts me that endings are thus formally unappealing to me – that more than beginning or ending, I enjoy continuing.” (83)

“Before I was a mother, I thought I was asking, How, then, can I survive forgetting so much?

Then I came to understand that the forgotten moments are the price of continued participation in life, a force indifferent to time.” (85)

- This hit hard when I read it.

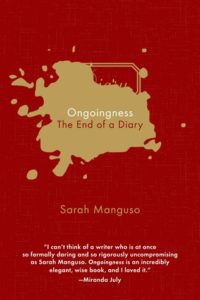

“Now I consider the diary a compilation of moments I’ll forget, their record finished in language as well as I could finish it – which is to say imperfectly.

Someday I might read about some of the moments I’ve forgotten, moments I’ve allowed myself to forget, that my brain was designed to forget, that I’ll be glad to have forgotten and be glad to rediscover as writing. The experience is no longer experience. It is writing. I am still writing.

And I’m forgetting everything. My goal now is to forget it all so that I’m clean for death. Just the vaguest memory of love, of participation in the great unity.” (86)

“Time punishes us by taking everything, but it also saves us – by taking everything.” (91)

“It was while reading a letter from a childhood friend who continues to provide healthcare to people in underserved communities that I realized the jig was up. If I was never going to place malaria pills into the hands of the destitute, I needed to get my act together. I had to be sure I wasn't keeping anything from the world that might help it along. If the point was to write things that prevent people from commiting suicide, the least I could do would be to read my own diary. Just in case.

I realize how grandiose that sounds, but when your job is to think and write about yourself, the stakes start to appear artificially, comically high. And they must, for without them, I wouldn't write at all. I’d spend the day reading the internet, I’d be about half-done by now.” (92)

- NTS: emotional family tree project

“But the even greater problem was that no individual diary entry had been written to make sense by itself. It led neither away from the previous day, nor toward the following day. It possessed no form separate from the greater form, which itself was almost formless – which itself was just accumulation, just day after day after day after day.” (93)

- // when I read my diary and am lost because I don’t remember context